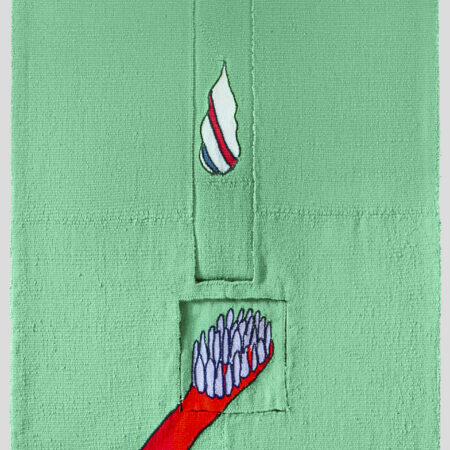

British textile artist Patrick Stratton combines tapestry weaving with automation to create tapestries that depict small everyday human movements. “My style of tapestry is focused on using a simple, graphic, pop-art aesthetic.” Still relatively new to the art world, he has already had international success and has exhibited in the UK and Italy.

What is your background in textiles?

I learnt Tapestry weaving on a short course at Morley College, I was inspired to do it when I took a year out from university and trying to do art on my own, and I then did a masters in Fine Art at City and Guilds London School of Art. My mum did it when I was very young so I thought I would give it a go, it turned out I absolutely loved it and still do.

What is it about tapestry that appeals to you?

For me personally there’s quite a lot of things that attract me to weaving, firstly, it’s linearity. How, through making points of colour through yarn and weft an image is made. I’m still fascinated by this, for the challenges that come from it- having to think about drawing through loads of horizontal lines-but also how it feels architecturally magical. This process I do builds an image while also building an object, it feels sculptural and like drawing at the same time.

The other reason is how much potential tapestry has as a medium. It is, fundamentally, one of the most basic methods of making textiles, which are ever-present in the world we live in. As a result, it has an astounding level of adaptability. Through my own haphazard experimentation I’ve found it can be stretched over forms, it can have neon attached into it, dipped into plaster, have a marble run shoved in it (something I want to return to) and made to move through motors. It’s crazy to think that I’ve only really scratched the surface of what tapestry can do and for me, I find that really exciting.

How do you describe your work?

I usually describe my work as mechanical tapestries, but if I’m honest that description never sits right. Perhaps Tapestry Automata fits better. Either way, my practice focuses on making moving tapestries through a combination of weaving and electronics.

How do you create a piece?

Each piece starts from a list I’ve made called “Things I Do Sometimes”. Made in the first lockdown, it was my attempt to list everything I do sometimes, no matter how boring or ever-present. This conceptual approach came from my fascination with writers like Samuel Beckett and conceptual art from the likes of artists like Douglas Huebler. I try to pick from the list as randomly as possible, but if I’m honest, sometimes I’ll pick one because I’ll get excited by a possible mechanism or some new material I can incorporate into tapestry (for example I jumped straight in to trying to make a kettle because I really wanted to try and put a smoke machine in a tapestry).

Once the subject is chosen, the next step is usually trying to make a composition. This is split into two parts usually, visual composition and mechanical composition.

Visual composition is focused on how I want the piece look. I start this process by doing a propositional drawing, usually in ink and very open ended. My style of tapestry is focused on using a simple, graphic, pop-art aesthetic so it helps sometimes to draw draft compositions are very bare bones. This helps to find what information is necessary in the composition to successfully depict an action.

From there, the rest of the visual composition part is done in the weaving stage, I like to keep this as open ended as possible so I can make decisions while I’m weaving my work.

Mechanical composition is much more complicated for me. This is when I try and work out how I want my pieces to move and how to fabricate it. It usually means making prototypes with Lego and cardboard, eventually using modelling software to design a frame and the mechanics.

Once the frame and mechanics are built I sort out the electronics (often losing my temper a couple of times in the process) and then making each tapestry part out of cardboard, and do a sort of draft run, seeing how the piece will look like once done, after that I weave each part individually and then put it all together.

Obviously this method doesn’t ever really stay the same, sometimes the tapestry parts are woven first because they have to be a specific size or sometimes the mechanics have to be redesigned or resized because the woven pieces ended up slightly different dimensions but that’s what makes it interesting and challenging.

Is the mechanical part of your art a challenge?

Definitely, besides the obvious pragmatic challenges of electronics, one of the most challenging parts of it is trying to work out how to replicate complex human movement. A lot of these motions we do like grating cheese or stepping in gum or even Hoovering require a lot of intricate parts, which I try my best to replicate. However, there’s also the other side of the coin, which is if the mechanics of my work works too well. When this happens it ends up disconcerting to look at, and a little creepy. When doing my work I’m constantly trying to find a balance between successful mechanics and not being too successful. I suppose I’m aiming for my work to barely work.

The other challenge of the mechanical part is incorporating the mechanics into the tapestry. While tapestry is very adaptable there is a limit to its adaptability. I’ve had numerous pieces where the compostion and the mechanics work but fall apart the moment they’re put together, which is always very frustrating.

Recently I’ve been trying to move away from using coding and electronics by making the movement in my work more mechanical than it already is by using gear systems. I’m excited about the recent developments in my work over the past few months but it has definitely been a challenge learning how to remake my art. Hopefully, the results will be worth it.

How long does a bigger piece take?

A bigger piece usually takes around a month, three weeks to weave all the parts, and then one to two very stressful week (or weeks) of coding, electronics, frame building and assembly.

What is your career highlight so far?

For me it would be being in shortlisted for the Ashurst emerging art prize, being at the ReA art fair in Milan and being shortlisted for the Cordis tapestry prize. Each of these were wonderful experiences that I’m very proud of.